Image 1 of 5

Image 1 of 5

Image 2 of 5

Image 2 of 5

Image 3 of 5

Image 3 of 5

Image 4 of 5

Image 4 of 5

Image 5 of 5

Image 5 of 5

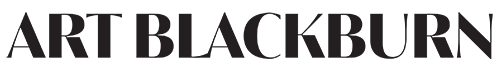

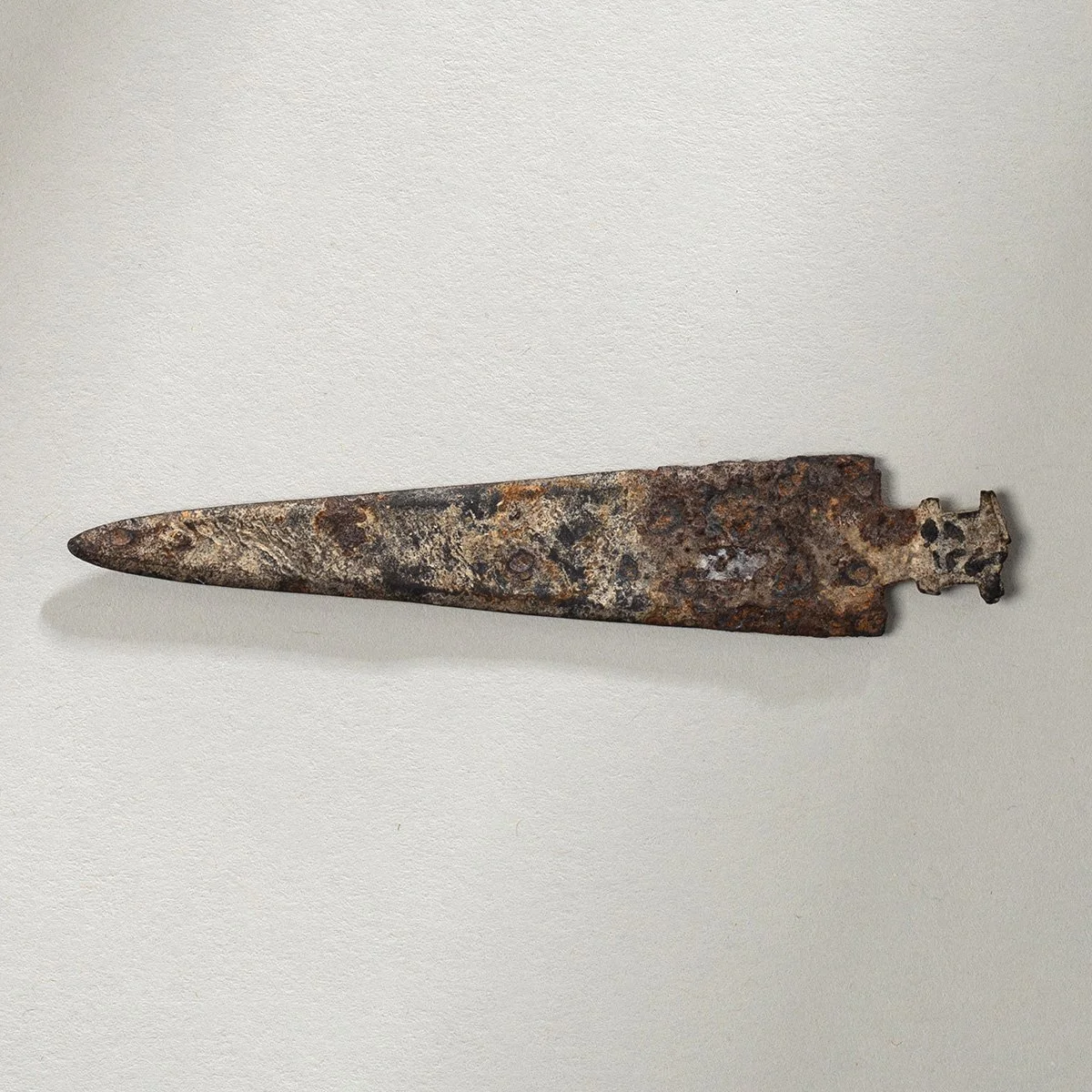

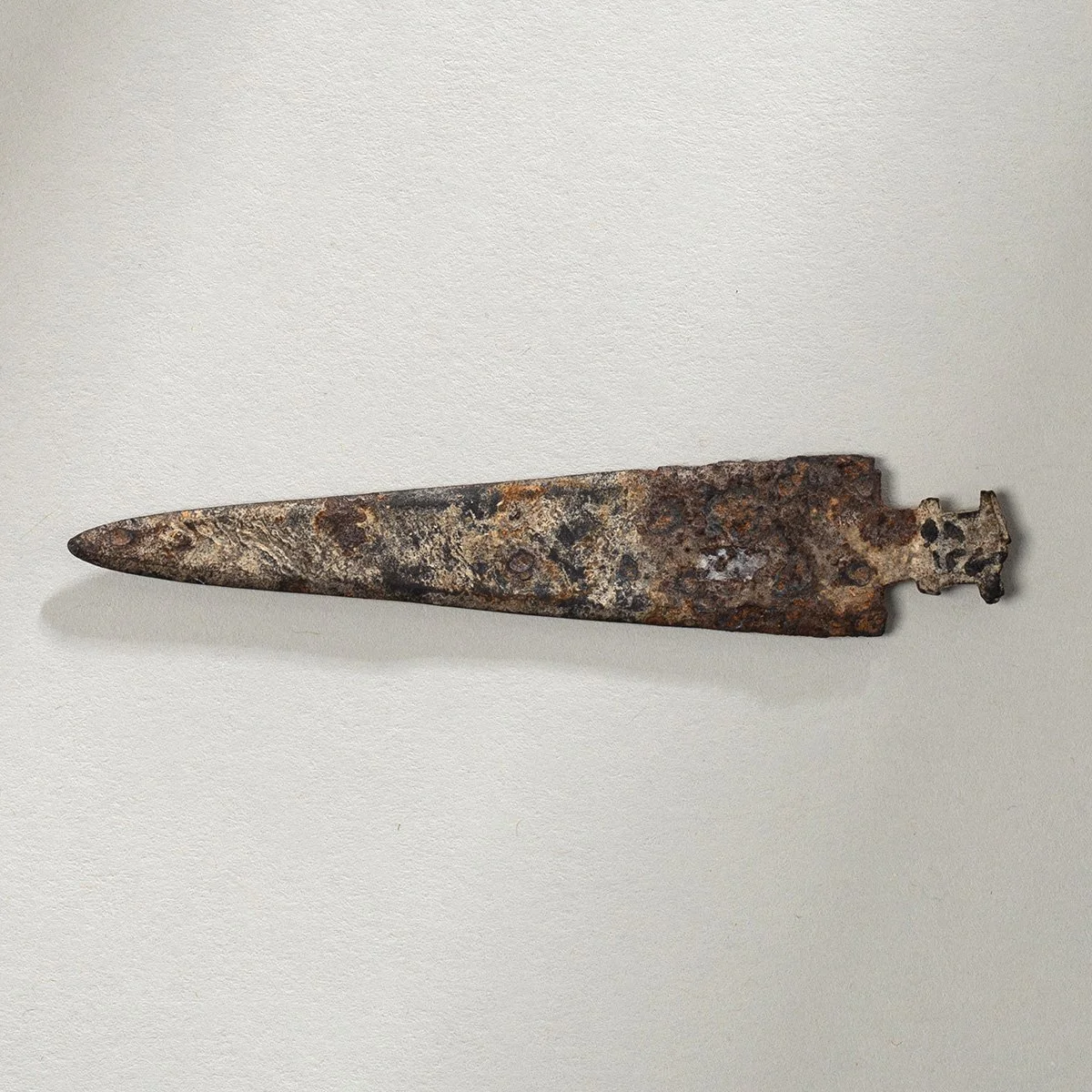

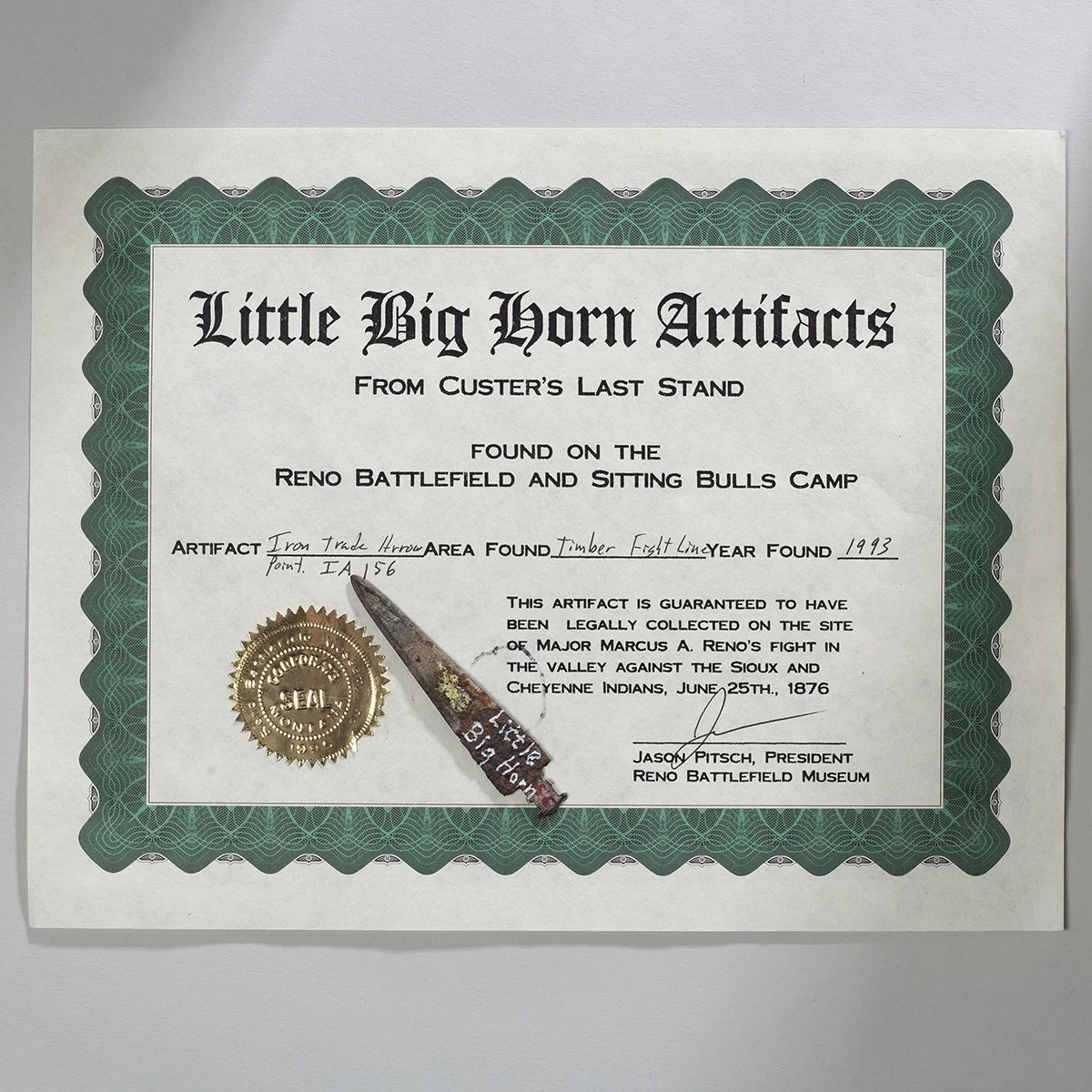

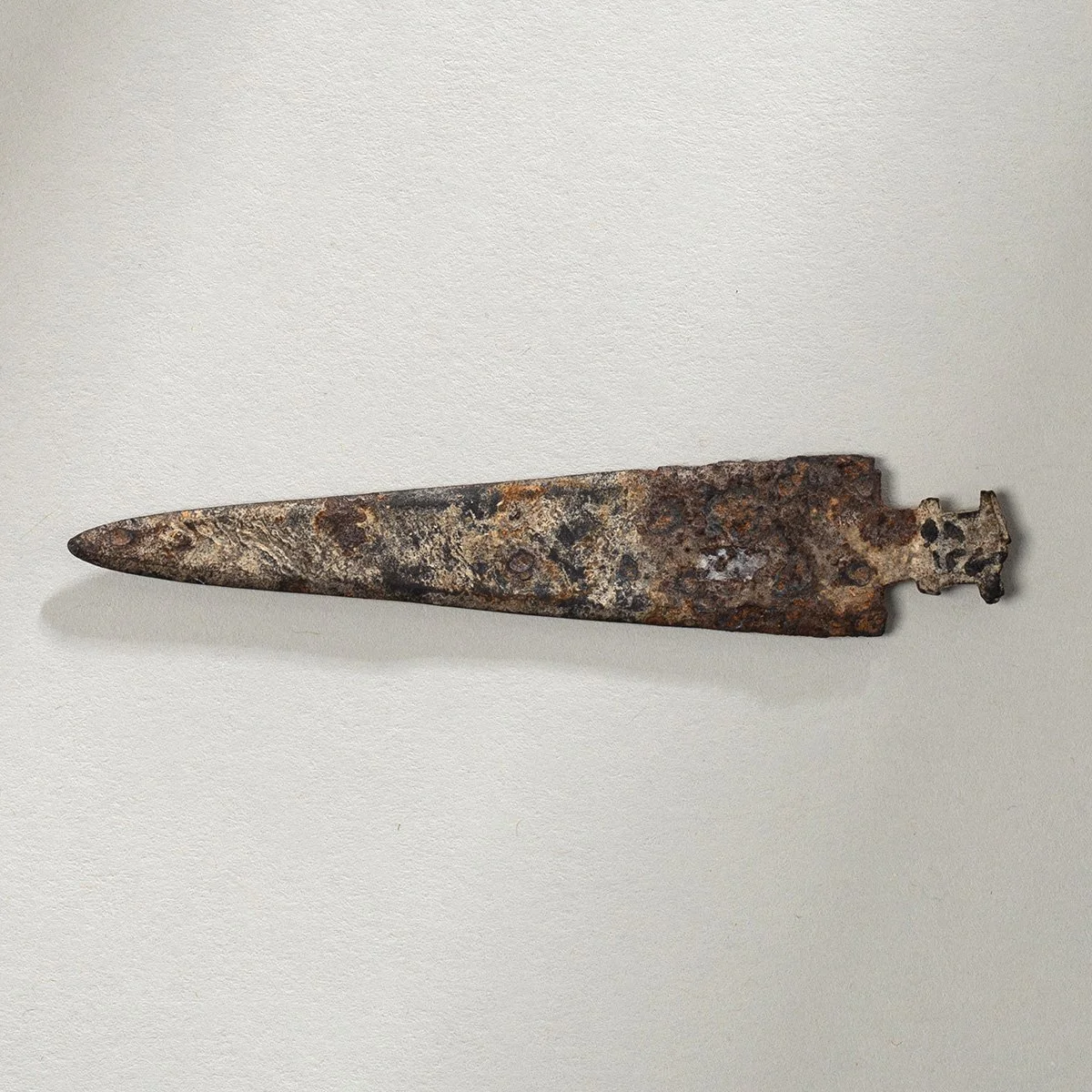

Iron Point from Custer's Last Stand 1 - SOLD

Found on the Reno Battlefield and Sitting Bulls Camp - Timber Fight Line

1870s

Provenance: Jason Pitsch, President of Reno Battlefield Museum

Found on private land with Topographical map etc where point was found and numbered COA etc.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass,[1][2] and commonly referred to as Custer’s Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapahotribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876.[3]

Most battles in the Great Sioux War, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn, were on lands those natives had taken from other tribes since 1851.[4][5][6][7] The Lakotas were there without consent from the local Crow tribe, which had a treaty on the area. Already in 1873, Crow chief Blackfoot had called for U.S. military actions against the native intruders.[8][9] The steady Lakota incursions into treaty areas belonging to the smaller tribes were a direct result of their displacement by the United States in and around Fort Laramie, as well as in reaction to white encroachment into the Black Hills, which the Lakota consider sacred.[10]This pre-existing Indian conflict provided a useful wedge for colonization, and ensured the United States a firm Indian alliance with the Arikaras[11]and the Crows during the Lakota Wars.[12][13][14]

The fight was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, and had been inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake). The U.S. 7th Cavalry, a force of 700 men, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer(a brevetted major general during the American Civil War), suffered a major defeat. Five of the 7th Cavalry’s twelve companies were wiped out, and Custer was killed, as were two of his brothers, his nephew, and his brother-in-law. The total U.S. casualty count included 268 dead and 55 severely wounded (6 died later from their wounds),[15]: 244 including 4 Crow Indian scouts and at least 2 Arikara Indian scouts.

Public response to the Great Sioux War varied in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Custer’s widow Libbie Custer soon worked to burnish her husband’s memory and during the following decades, Custer and his troops came to be considered heroic figures in American history. The battle and Custer’s actions in particular have been studied extensively by historians.[16] By the 1930s Custer’s heroic public image began to tarnish after the death of Elizabeth Bacon (Libby) Custer in 1933 at the age of 90 and the publication of Glory Hunter - The Life of General Custer by Frederic F. Van de Water, which was the first book to depict Custer in unheroic terms.[17] The timing of both instances, combined with the cynicism of an economic depression and historical revisionism, led to a more jaded view of Custer and his defeat on the banks of the Little Bighorn River.[17] Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument honors those who fought on both sides.

Found on the Reno Battlefield and Sitting Bulls Camp - Timber Fight Line

1870s

Provenance: Jason Pitsch, President of Reno Battlefield Museum

Found on private land with Topographical map etc where point was found and numbered COA etc.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass,[1][2] and commonly referred to as Custer’s Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapahotribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876.[3]

Most battles in the Great Sioux War, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn, were on lands those natives had taken from other tribes since 1851.[4][5][6][7] The Lakotas were there without consent from the local Crow tribe, which had a treaty on the area. Already in 1873, Crow chief Blackfoot had called for U.S. military actions against the native intruders.[8][9] The steady Lakota incursions into treaty areas belonging to the smaller tribes were a direct result of their displacement by the United States in and around Fort Laramie, as well as in reaction to white encroachment into the Black Hills, which the Lakota consider sacred.[10]This pre-existing Indian conflict provided a useful wedge for colonization, and ensured the United States a firm Indian alliance with the Arikaras[11]and the Crows during the Lakota Wars.[12][13][14]

The fight was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, and had been inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake). The U.S. 7th Cavalry, a force of 700 men, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer(a brevetted major general during the American Civil War), suffered a major defeat. Five of the 7th Cavalry’s twelve companies were wiped out, and Custer was killed, as were two of his brothers, his nephew, and his brother-in-law. The total U.S. casualty count included 268 dead and 55 severely wounded (6 died later from their wounds),[15]: 244 including 4 Crow Indian scouts and at least 2 Arikara Indian scouts.

Public response to the Great Sioux War varied in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Custer’s widow Libbie Custer soon worked to burnish her husband’s memory and during the following decades, Custer and his troops came to be considered heroic figures in American history. The battle and Custer’s actions in particular have been studied extensively by historians.[16] By the 1930s Custer’s heroic public image began to tarnish after the death of Elizabeth Bacon (Libby) Custer in 1933 at the age of 90 and the publication of Glory Hunter - The Life of General Custer by Frederic F. Van de Water, which was the first book to depict Custer in unheroic terms.[17] The timing of both instances, combined with the cynicism of an economic depression and historical revisionism, led to a more jaded view of Custer and his defeat on the banks of the Little Bighorn River.[17] Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument honors those who fought on both sides.

Found on the Reno Battlefield and Sitting Bulls Camp - Timber Fight Line

1870s

Provenance: Jason Pitsch, President of Reno Battlefield Museum

Found on private land with Topographical map etc where point was found and numbered COA etc.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass,[1][2] and commonly referred to as Custer’s Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapahotribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876.[3]

Most battles in the Great Sioux War, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn, were on lands those natives had taken from other tribes since 1851.[4][5][6][7] The Lakotas were there without consent from the local Crow tribe, which had a treaty on the area. Already in 1873, Crow chief Blackfoot had called for U.S. military actions against the native intruders.[8][9] The steady Lakota incursions into treaty areas belonging to the smaller tribes were a direct result of their displacement by the United States in and around Fort Laramie, as well as in reaction to white encroachment into the Black Hills, which the Lakota consider sacred.[10]This pre-existing Indian conflict provided a useful wedge for colonization, and ensured the United States a firm Indian alliance with the Arikaras[11]and the Crows during the Lakota Wars.[12][13][14]

The fight was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, and had been inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake). The U.S. 7th Cavalry, a force of 700 men, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer(a brevetted major general during the American Civil War), suffered a major defeat. Five of the 7th Cavalry’s twelve companies were wiped out, and Custer was killed, as were two of his brothers, his nephew, and his brother-in-law. The total U.S. casualty count included 268 dead and 55 severely wounded (6 died later from their wounds),[15]: 244 including 4 Crow Indian scouts and at least 2 Arikara Indian scouts.

Public response to the Great Sioux War varied in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Custer’s widow Libbie Custer soon worked to burnish her husband’s memory and during the following decades, Custer and his troops came to be considered heroic figures in American history. The battle and Custer’s actions in particular have been studied extensively by historians.[16] By the 1930s Custer’s heroic public image began to tarnish after the death of Elizabeth Bacon (Libby) Custer in 1933 at the age of 90 and the publication of Glory Hunter - The Life of General Custer by Frederic F. Van de Water, which was the first book to depict Custer in unheroic terms.[17] The timing of both instances, combined with the cynicism of an economic depression and historical revisionism, led to a more jaded view of Custer and his defeat on the banks of the Little Bighorn River.[17] Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument honors those who fought on both sides.