Image 1 of 11

Image 1 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 11 of 11

Image 11 of 11

Ceremonial Bonito Sculpture - SOLD

Makira Province, Southeastern Solomon Islands

Mid to Late19th century

Wood, nautilus shell, natural pigments

Length:18.75 inches (47.5 cm)

Provenance: Chris and Anna Thorpe personal collection - Sydney, Australia.

Among the archipelago of islands that comprise the Southeastern Solomon Islands, life for its native inhabitants during the 19th century was comparatively peaceful in contrast to their more aggressive neighbors to the West, lending an ease and exuberance to their culture that was reflected in their flourishing artforms. As a marine culture, the community built their homes and settlements close to the shoreline, creating a close connection between their daily life and the ocean. They looked to the sea for sustenance, and their traditional myths and associated religious elements were based upon the abundance and diversity of the surrounding ocean. The center of the community’s cultural life and social organization was the men’s house or Aofa, which was a grand structure built to house the large and elaborately decorated sacred canoes that were used to hunt at sea for bonito (a tuna-like fish). The bonito are a powerful fish; scaleless, smooth skinned, and copiously filled with red blood like that of humans. So close were the connections between humans and bonito that the maraufu and malachu initiation ceremonies of the bonito cult included the directing of blood from the bonito into the mouths of the initiates. The grand aofa also housed life-sized wooden sculptures of bonito fish that were secured among the rafters, alongside carvings of sharks, frigate birds, and monumental portrayals of human ancestors, as well as suspended rows of trophy bonito skeletons from earlier ceremonial feasts.

The bonito hunt itself was an important stage in a young man’s life whereby he would gain important ancestral knowledge through the rites and rituals associated with the hunt. Bonito are difficult to catch, and it was believed they could only be successfully caught when their protective marine deities intervened and permitted their ensnarement by humans. Bonito band into a highly energized school to prey on shoals of small baitfish, working together to aggressively attack the shoal and drive it upwards towards the surface, where fish hawks, terns, frigate birds and sharks enter the fray with the resulting churning waters attracting hopeful fishermen. These bonito-instigated events could last for hours or dissipate quickly and were considered to be episodes of almost supernatural occurrence. It was the seasonal arrival of the bonito that signaled the start of initiation events, and the wooden sculptures portraying bonito and frigate birds were then removed from the aofa and secured to elaborately decorated elevated dance platforms erected along the shoreline, facing out to sea, for ceremonial performances.

The bonito sculpture presented here was created by a skilled carver who masterfully portrayed the fish as in its underwater environment. With fins erect, the essence of the bonito’s form and powerful speed were perfectly captured by the artist, for he would have had an intimate knowledge of the bonito and its behavior and would himself have been initiated into the bonito cult and participated in the bonito hunt during his lifetime. The surface of the sculpture is inset with carefully cut sections of lustrous shell inlays, rendered from the shell of the chambered-nautilus and secured with a durable natural adhesive obtained from the paranarium nut. Like other carvings from the Southeastern Solomons, the shell inlays are strikingly highlighted against the black painted surface of the sculpture. A series of carved parallel ridges, portraying the natural striped patterns of the bonito, are painted with traces of white lime pigment that further enhance the sculpture’s form. A pair of sharks carved in relief are depicted above the mouth of the bonito and highlight the importance of this animal within local mythology, with many traditional stories told of the powerful shark god Karamanua and this sea spirit’s important role in fishing and human affairs.

Prior to the broader arrival of Europeans in the late 19th century, this scattering of idyllic verdant islands with their surrounding aquamarine waters and equatorial sky above, comprised the known universe for its inhabitants, and from this tiny cosmos evolved a vast spiritual world and complex mythology; one in which the sea was home to a pantheon of ancestral ghosts and sea spirits, including those of the frigate bird, shark, sea turtle, and a diverse array of other deified marine animals. It was however the sacred bonito that the people most closely identified themselves with and which their culture rested upon, forming the foundation for the communities’ ceremonial rites and rituals throughout the initiate’s lifetime. Even in death, the spirit of the bonito served the initiates and the community, for the bones of the deceased were interred inside special wooden reliquaries, skillfully carved in the likeness of the bonito and given a permanent place of honor inside the community Aofa.

Makira Province, Southeastern Solomon Islands

Mid to Late19th century

Wood, nautilus shell, natural pigments

Length:18.75 inches (47.5 cm)

Provenance: Chris and Anna Thorpe personal collection - Sydney, Australia.

Among the archipelago of islands that comprise the Southeastern Solomon Islands, life for its native inhabitants during the 19th century was comparatively peaceful in contrast to their more aggressive neighbors to the West, lending an ease and exuberance to their culture that was reflected in their flourishing artforms. As a marine culture, the community built their homes and settlements close to the shoreline, creating a close connection between their daily life and the ocean. They looked to the sea for sustenance, and their traditional myths and associated religious elements were based upon the abundance and diversity of the surrounding ocean. The center of the community’s cultural life and social organization was the men’s house or Aofa, which was a grand structure built to house the large and elaborately decorated sacred canoes that were used to hunt at sea for bonito (a tuna-like fish). The bonito are a powerful fish; scaleless, smooth skinned, and copiously filled with red blood like that of humans. So close were the connections between humans and bonito that the maraufu and malachu initiation ceremonies of the bonito cult included the directing of blood from the bonito into the mouths of the initiates. The grand aofa also housed life-sized wooden sculptures of bonito fish that were secured among the rafters, alongside carvings of sharks, frigate birds, and monumental portrayals of human ancestors, as well as suspended rows of trophy bonito skeletons from earlier ceremonial feasts.

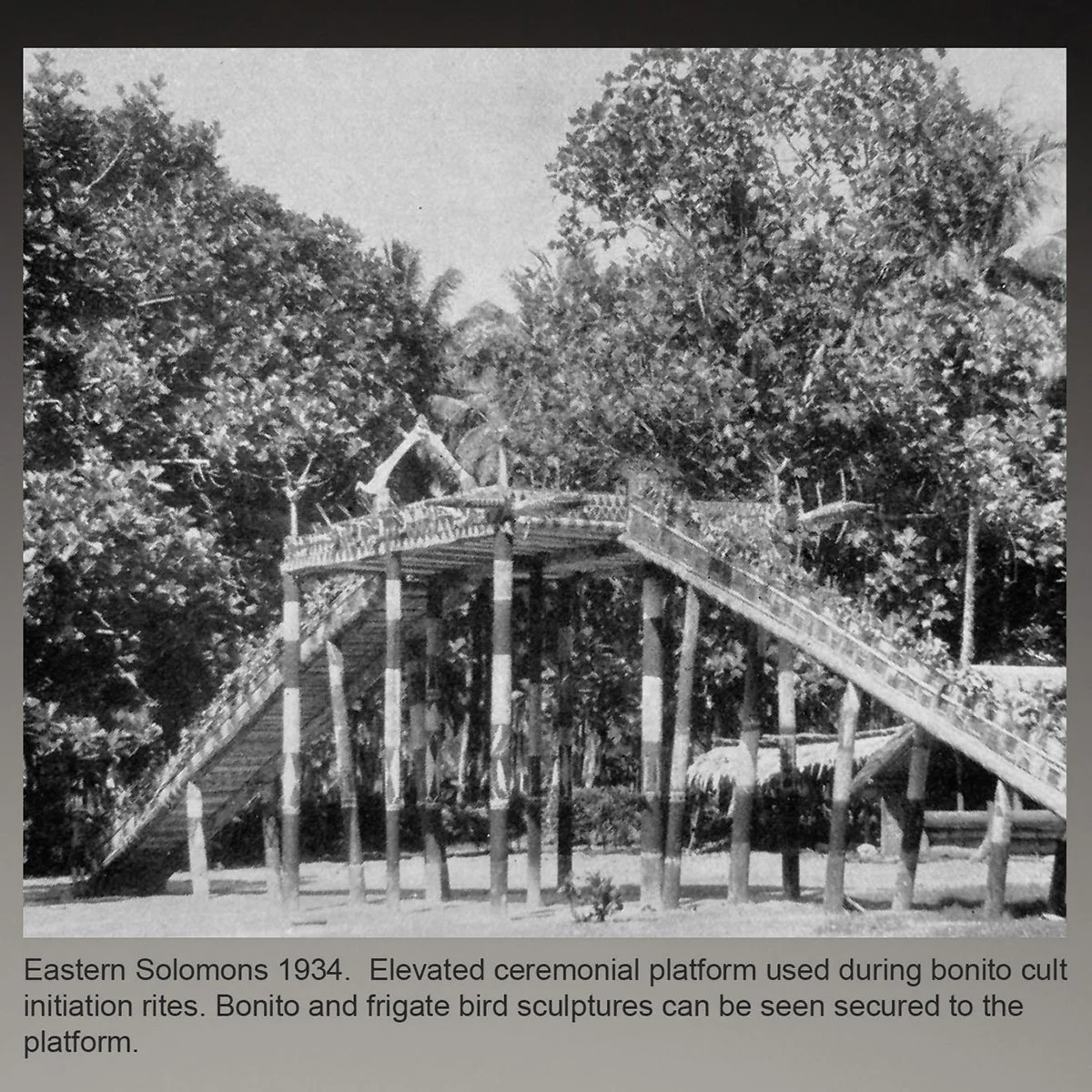

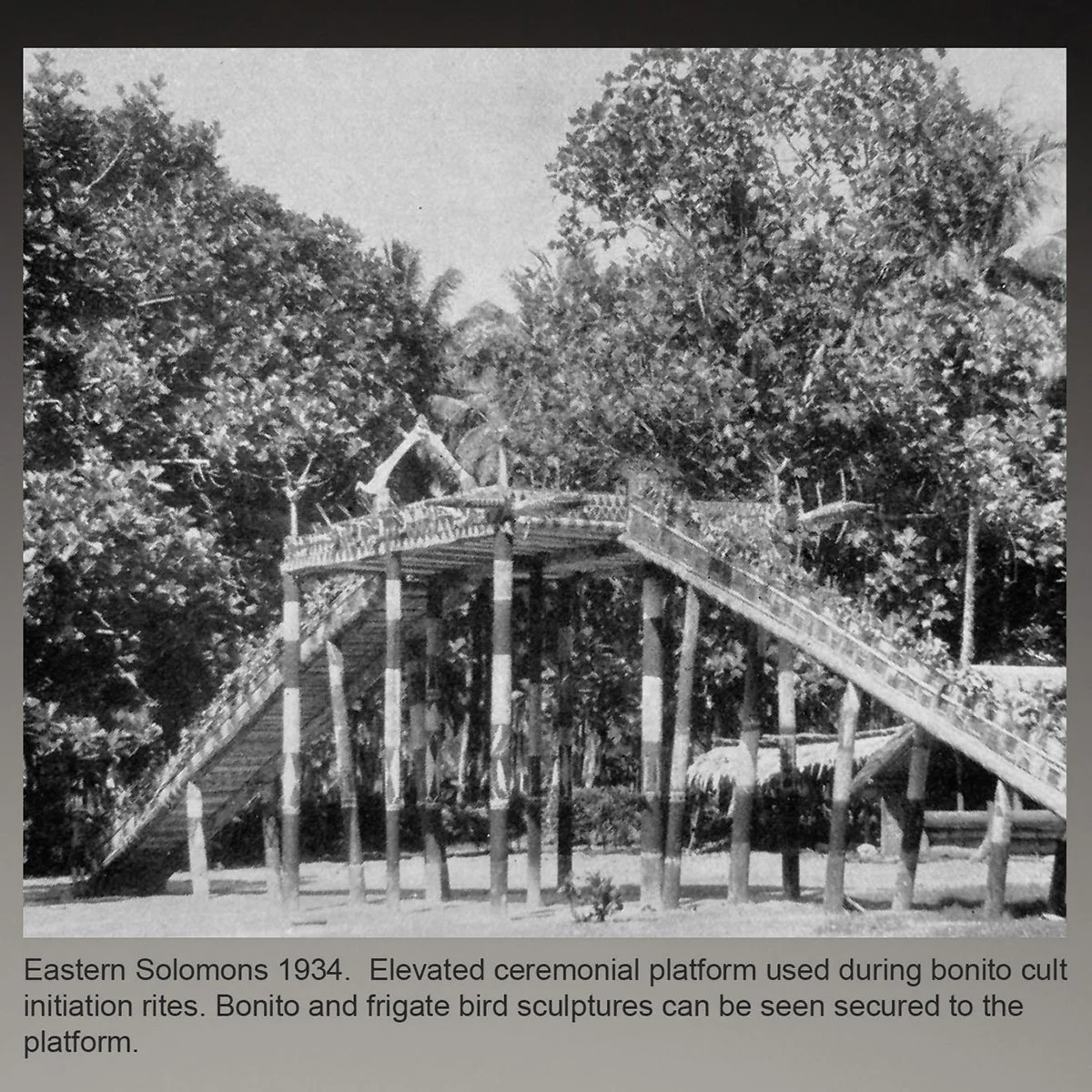

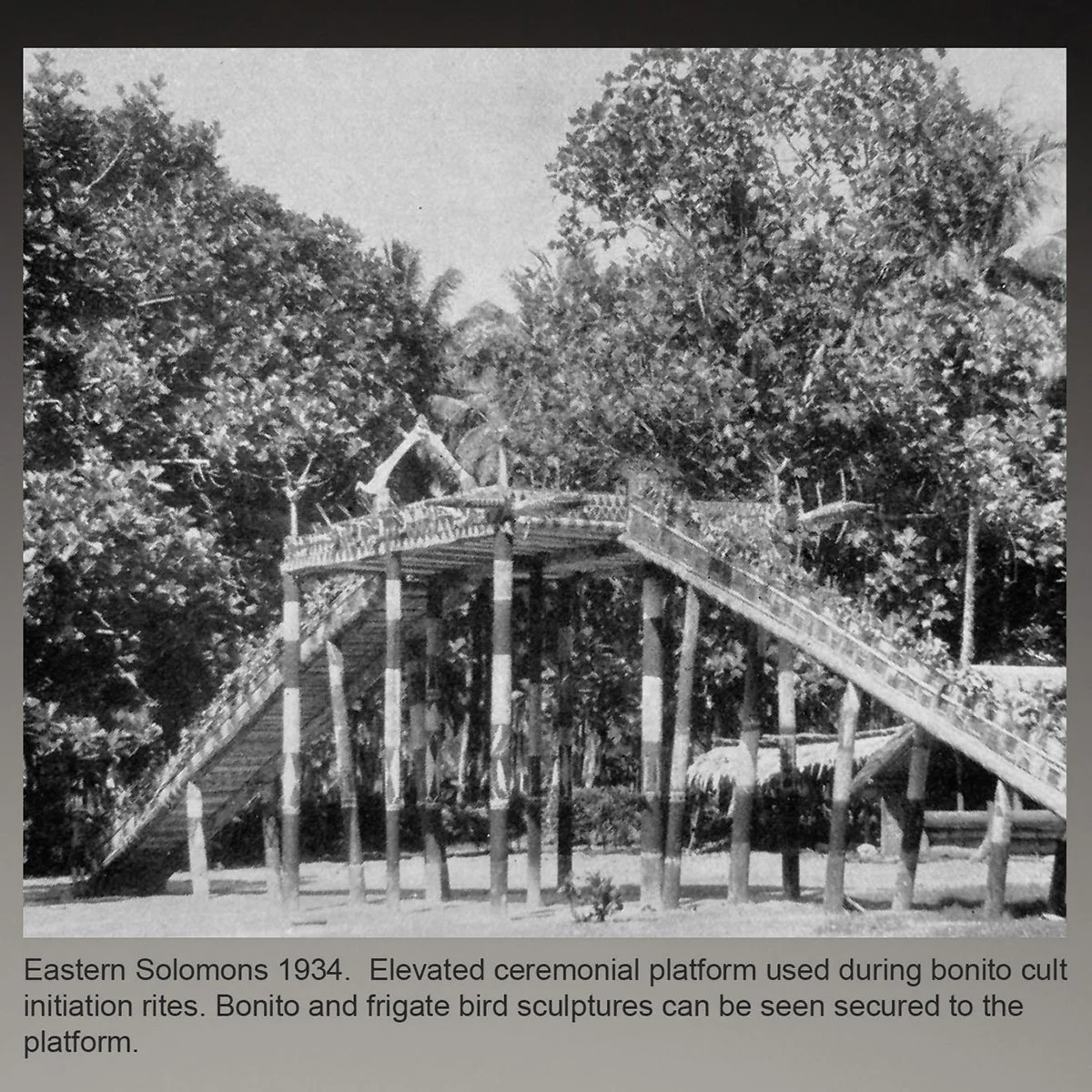

The bonito hunt itself was an important stage in a young man’s life whereby he would gain important ancestral knowledge through the rites and rituals associated with the hunt. Bonito are difficult to catch, and it was believed they could only be successfully caught when their protective marine deities intervened and permitted their ensnarement by humans. Bonito band into a highly energized school to prey on shoals of small baitfish, working together to aggressively attack the shoal and drive it upwards towards the surface, where fish hawks, terns, frigate birds and sharks enter the fray with the resulting churning waters attracting hopeful fishermen. These bonito-instigated events could last for hours or dissipate quickly and were considered to be episodes of almost supernatural occurrence. It was the seasonal arrival of the bonito that signaled the start of initiation events, and the wooden sculptures portraying bonito and frigate birds were then removed from the aofa and secured to elaborately decorated elevated dance platforms erected along the shoreline, facing out to sea, for ceremonial performances.

The bonito sculpture presented here was created by a skilled carver who masterfully portrayed the fish as in its underwater environment. With fins erect, the essence of the bonito’s form and powerful speed were perfectly captured by the artist, for he would have had an intimate knowledge of the bonito and its behavior and would himself have been initiated into the bonito cult and participated in the bonito hunt during his lifetime. The surface of the sculpture is inset with carefully cut sections of lustrous shell inlays, rendered from the shell of the chambered-nautilus and secured with a durable natural adhesive obtained from the paranarium nut. Like other carvings from the Southeastern Solomons, the shell inlays are strikingly highlighted against the black painted surface of the sculpture. A series of carved parallel ridges, portraying the natural striped patterns of the bonito, are painted with traces of white lime pigment that further enhance the sculpture’s form. A pair of sharks carved in relief are depicted above the mouth of the bonito and highlight the importance of this animal within local mythology, with many traditional stories told of the powerful shark god Karamanua and this sea spirit’s important role in fishing and human affairs.

Prior to the broader arrival of Europeans in the late 19th century, this scattering of idyllic verdant islands with their surrounding aquamarine waters and equatorial sky above, comprised the known universe for its inhabitants, and from this tiny cosmos evolved a vast spiritual world and complex mythology; one in which the sea was home to a pantheon of ancestral ghosts and sea spirits, including those of the frigate bird, shark, sea turtle, and a diverse array of other deified marine animals. It was however the sacred bonito that the people most closely identified themselves with and which their culture rested upon, forming the foundation for the communities’ ceremonial rites and rituals throughout the initiate’s lifetime. Even in death, the spirit of the bonito served the initiates and the community, for the bones of the deceased were interred inside special wooden reliquaries, skillfully carved in the likeness of the bonito and given a permanent place of honor inside the community Aofa.

Makira Province, Southeastern Solomon Islands

Mid to Late19th century

Wood, nautilus shell, natural pigments

Length:18.75 inches (47.5 cm)

Provenance: Chris and Anna Thorpe personal collection - Sydney, Australia.

Among the archipelago of islands that comprise the Southeastern Solomon Islands, life for its native inhabitants during the 19th century was comparatively peaceful in contrast to their more aggressive neighbors to the West, lending an ease and exuberance to their culture that was reflected in their flourishing artforms. As a marine culture, the community built their homes and settlements close to the shoreline, creating a close connection between their daily life and the ocean. They looked to the sea for sustenance, and their traditional myths and associated religious elements were based upon the abundance and diversity of the surrounding ocean. The center of the community’s cultural life and social organization was the men’s house or Aofa, which was a grand structure built to house the large and elaborately decorated sacred canoes that were used to hunt at sea for bonito (a tuna-like fish). The bonito are a powerful fish; scaleless, smooth skinned, and copiously filled with red blood like that of humans. So close were the connections between humans and bonito that the maraufu and malachu initiation ceremonies of the bonito cult included the directing of blood from the bonito into the mouths of the initiates. The grand aofa also housed life-sized wooden sculptures of bonito fish that were secured among the rafters, alongside carvings of sharks, frigate birds, and monumental portrayals of human ancestors, as well as suspended rows of trophy bonito skeletons from earlier ceremonial feasts.

The bonito hunt itself was an important stage in a young man’s life whereby he would gain important ancestral knowledge through the rites and rituals associated with the hunt. Bonito are difficult to catch, and it was believed they could only be successfully caught when their protective marine deities intervened and permitted their ensnarement by humans. Bonito band into a highly energized school to prey on shoals of small baitfish, working together to aggressively attack the shoal and drive it upwards towards the surface, where fish hawks, terns, frigate birds and sharks enter the fray with the resulting churning waters attracting hopeful fishermen. These bonito-instigated events could last for hours or dissipate quickly and were considered to be episodes of almost supernatural occurrence. It was the seasonal arrival of the bonito that signaled the start of initiation events, and the wooden sculptures portraying bonito and frigate birds were then removed from the aofa and secured to elaborately decorated elevated dance platforms erected along the shoreline, facing out to sea, for ceremonial performances.

The bonito sculpture presented here was created by a skilled carver who masterfully portrayed the fish as in its underwater environment. With fins erect, the essence of the bonito’s form and powerful speed were perfectly captured by the artist, for he would have had an intimate knowledge of the bonito and its behavior and would himself have been initiated into the bonito cult and participated in the bonito hunt during his lifetime. The surface of the sculpture is inset with carefully cut sections of lustrous shell inlays, rendered from the shell of the chambered-nautilus and secured with a durable natural adhesive obtained from the paranarium nut. Like other carvings from the Southeastern Solomons, the shell inlays are strikingly highlighted against the black painted surface of the sculpture. A series of carved parallel ridges, portraying the natural striped patterns of the bonito, are painted with traces of white lime pigment that further enhance the sculpture’s form. A pair of sharks carved in relief are depicted above the mouth of the bonito and highlight the importance of this animal within local mythology, with many traditional stories told of the powerful shark god Karamanua and this sea spirit’s important role in fishing and human affairs.

Prior to the broader arrival of Europeans in the late 19th century, this scattering of idyllic verdant islands with their surrounding aquamarine waters and equatorial sky above, comprised the known universe for its inhabitants, and from this tiny cosmos evolved a vast spiritual world and complex mythology; one in which the sea was home to a pantheon of ancestral ghosts and sea spirits, including those of the frigate bird, shark, sea turtle, and a diverse array of other deified marine animals. It was however the sacred bonito that the people most closely identified themselves with and which their culture rested upon, forming the foundation for the communities’ ceremonial rites and rituals throughout the initiate’s lifetime. Even in death, the spirit of the bonito served the initiates and the community, for the bones of the deceased were interred inside special wooden reliquaries, skillfully carved in the likeness of the bonito and given a permanent place of honor inside the community Aofa.