Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

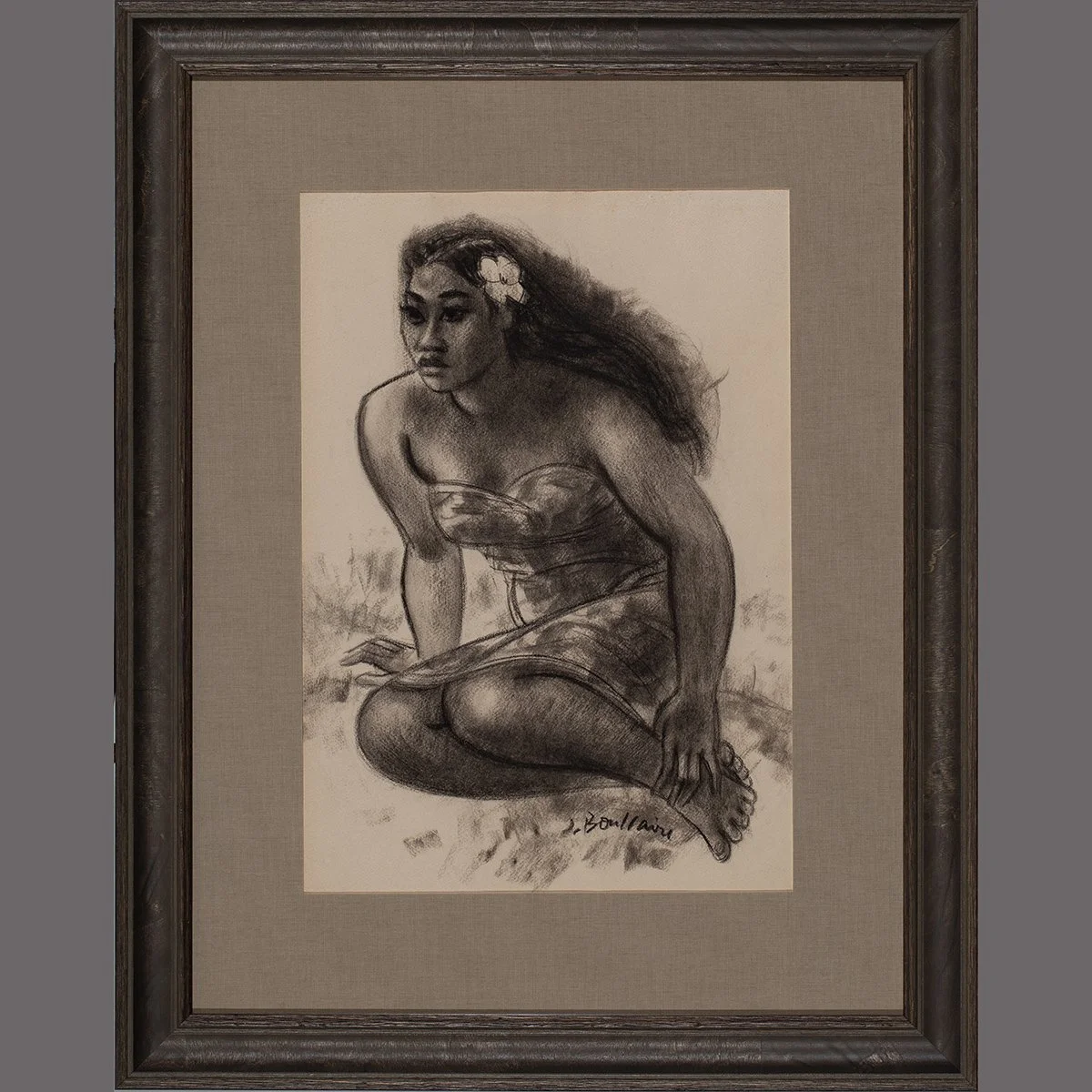

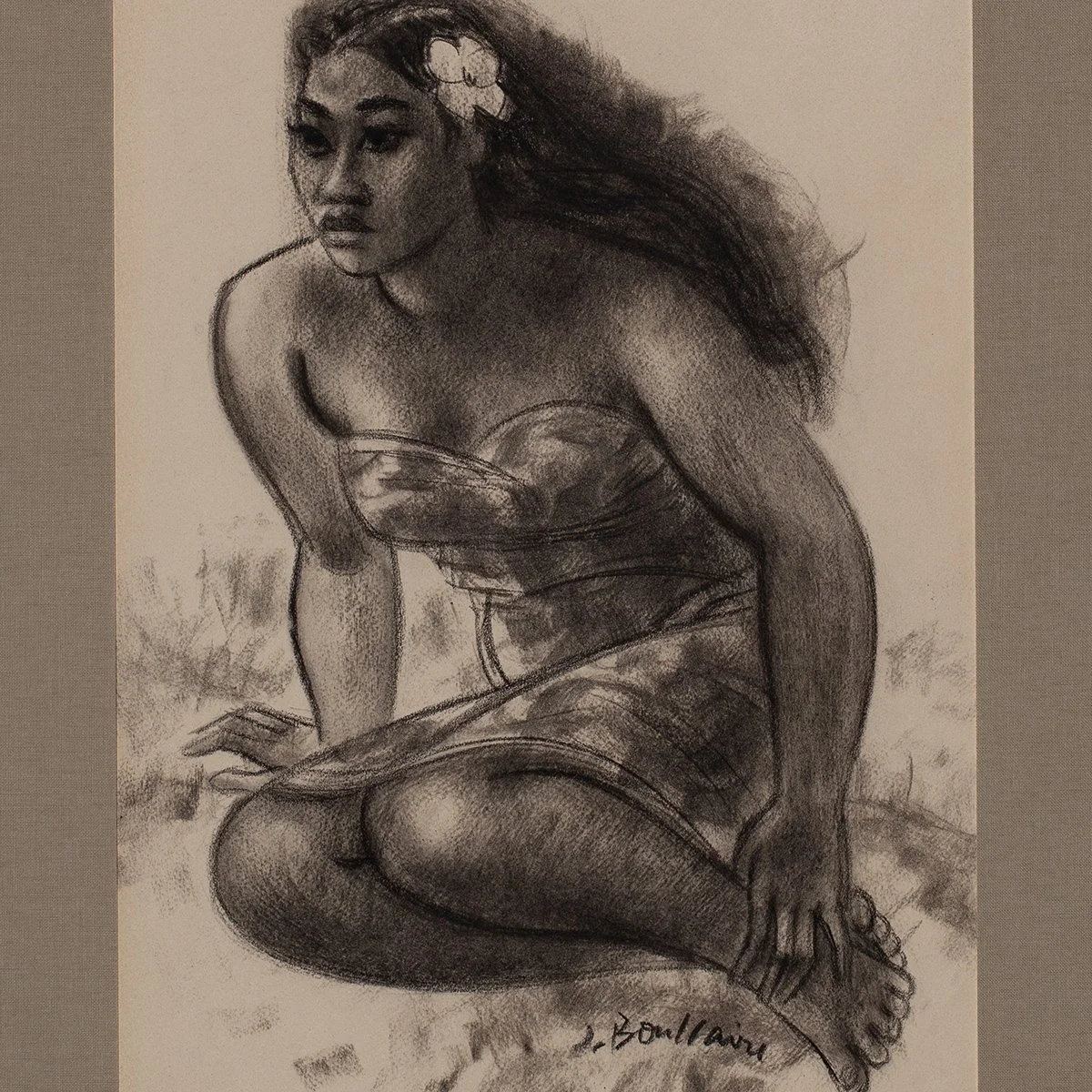

Jacques Boullaire Tahitian Vahine

Charcoal on paper

1950s

Height 23" Width 18" including frame, image Height 14 1/2" Width 10"

Provenance: Private collection Paris

Born in 1893, the eldest child of a family of wealthy Parisian lawyers, Jacques Boullaire loved to draw in his childhood and it was a passion that would remain with him throughout his life. In the book, ‘Tahiti a Sketchbook’ dedicated to his life and work, his daughter Aiu Deschamps-Boullaire describes the young Jacques thus: ‘…a dreamer who spent his days collecting insects in the garden of the family’s summer house near Reims and his evenings quietly contemplating the images illuminated by the family’s magic lantern in the darkness of the sitting room.’

Though it was traditional in an advantaged position such as his to follow the father and grandfather into the profession of law, this was not to be his course and at any rate the First World War intervened and he became a fighter pilot and remarkably so since he had poor eye-sight and suffered from myopia. Many of his fellow pilots perished but Boullaire survived. He kept in touch with himself as an artist by painting humorous scenes on the body of his plane.

After the war, Jacques, still a young man, could while away his time aided by the luxuries that came from belonging to a family of substantial wealth. All the past-times and the dalliances of the priviledged were available. His sister married Louis Renault, one of the founders of the Renault car company, who had built an incredible fantasy mansion and there he could stay and enjoy the sensuous and romantic delights of a life-style by the sea. Those who knew him accepted himas a dreamer, a thinker, someone of introspection and quiet reverie.

Yet he left the ease and security to begin a new life in Paris with no secure income. He took advertising jobs to survive and Louis Renault, trying to help his brother in law and bring him back into the mainstream, made him Director of Advertising at Renault. It was short lived. Boullaire loved Paris and his life as an artist began in Montmartre. He taught himself the difficult and challenging techniques of making artist’s original prints, first with woodcuts, and then etching onto copper. At this time he came to know and make friends with other print makers: Chiéze, Cami, Decares, and the Englishman, Stanley William Hayter and John Buckland Wright who was originally from New Zealand.

It was also during this period in 1935, that Boullaire met the woman who would inspire him, influence him deeply, and who would become his wife, Anne Hervé; the daughter of the Admistrator of Tuamotus, she had just arrived in Paris after twenty five years living away from European civilization on a Pacific island, and in Paris she walked the streets barefooted. And she too was an artist, a painter, and the two of them could share their passion, increasingly focussing their lives upon simple and naturalistic aims.

And so, to Tahiti. But first of all this was an experience in which, though it was familiar to Anne, Jacques had to find himself. All was so different, the essence of nature there and its powerfully coloured intensity was so different to Paris. The women too were so differnt in their attitude and physical being. On their return to France Boullaire began work on illustrating the ‘Marriage of Loti’. And then Anne gave birth to a daughter that they named ‘Aiv’ which means ‘baby’ in Tahitian.

How grim it must have been for him to be then faced with another war, and with its nullifying effect on the professional art world. He was not to fight in this one, but the family had to survive great hardships with little money. In the south of France they tried to live a life of self-sufficiency, growing their own food, and Anne as a consquence Ane increasingly had less time for her own painting.

After the war the family returned to Paris and Jacques set about working as an illustrator, receiving commissions from publishers of selct editions. Publications included ‘La Symphonie Pastorale’ by André Gide, Flaubert’s ‘Bouvard et Pecouchet’, and Proust’s ‘A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur’.

The life-style of the Boullaire family, its lack of materialism and its simplicity, the love of aesthetics to a degree that evokes the spiritual, the working on the land for self-sufficency during the war, has strong similarities in its aims and ideals to those that became so important to those who were authentically involved in the hippy movement that was to follow later in the century in the 1960s. The Boullaire’s, and it is reminiscent too of the gypsy ways of the earlier English artist, Augustus John, took in the Summer months to living in a caravan and travelling wherever the fancy took them – Boullaire always drawing.

In 1949 the Boullaires returned to Tahiti and this time for a much longer stay; the one year originally planned for turned into four. They made the lon jouney by boat via Portugal, the Antilles, and Panama. Their first sensing of their approach to Tahiti was not from eyesight but from the floral perfume brought to them by the sea breeze. Boullaire travelled through the island, drawing and watercolouring incessantly and perfecting his imagery of the Tahitian people in their naturak relaxed poses and habitat. The life could be idyllic. Jacques got on with the people and though he had little of the language his wife was fluent. He would always try to communicate with them as they allowed him to make his drawings of them, either formally posing (which could bore them), or just going about their ordinary lives. Though the family still tried to be self-sufficient and this took up much of Anne’s time, she too wqas painting again, mainly landscapes in pastel.

In Papeete they were invited by Princess Takau to live in the home of her mother, the queen. On the island of Bora Bora they stayed with their friend Jacqueline and Bernard Villaret and on Moorea they camped out on the beaches.

The family returned to Paris in 1952. He had a final stay in Tahiti fourteen years later and though now he was elderly and with fragile health he still worked.

Boullaire died in Paris in 1972. He was at his desk, still working, an engraving needle in his hand. In this classic image of a Tahitian woman or vahine, the artist skill is at his peak.

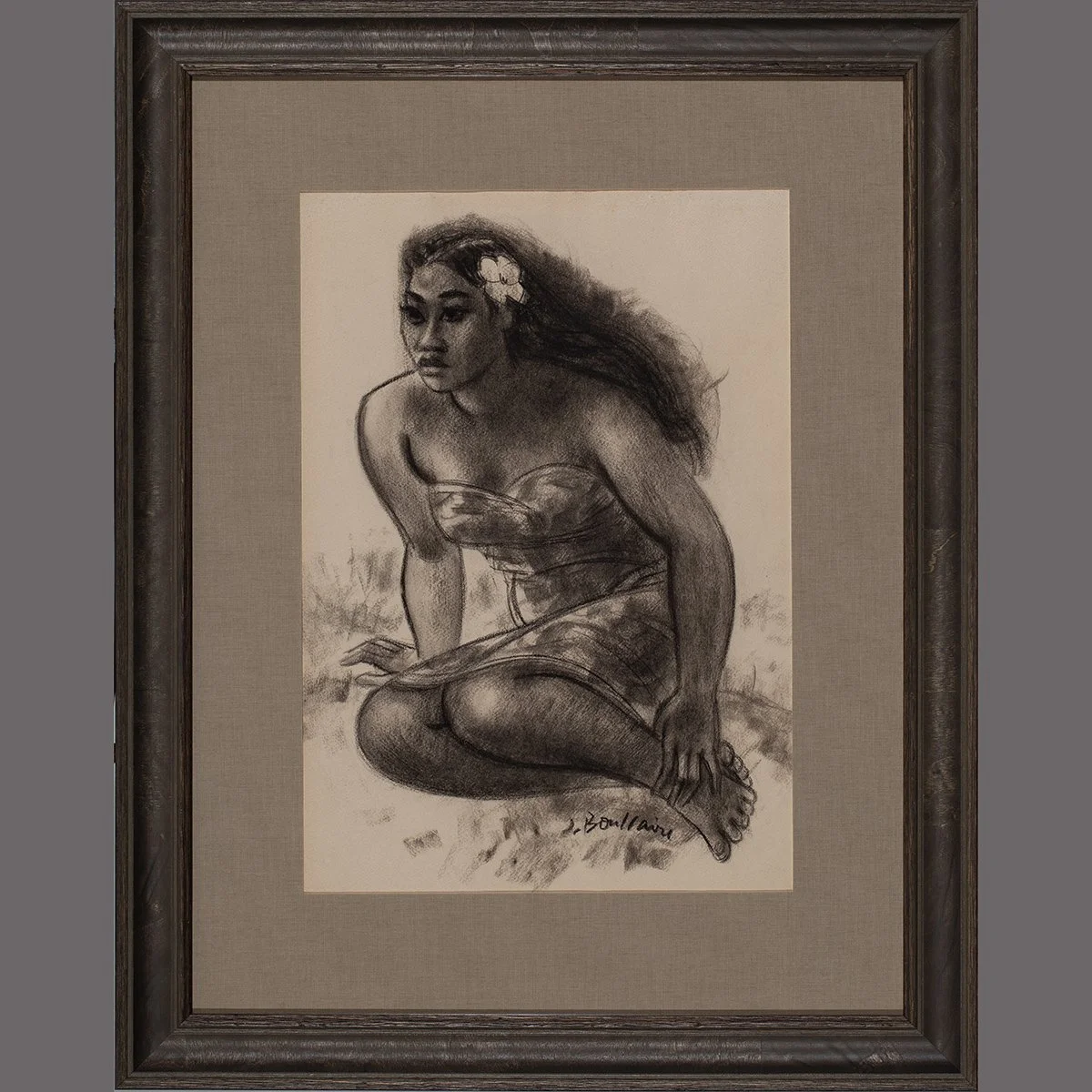

Charcoal on paper

1950s

Height 23" Width 18" including frame, image Height 14 1/2" Width 10"

Provenance: Private collection Paris

Born in 1893, the eldest child of a family of wealthy Parisian lawyers, Jacques Boullaire loved to draw in his childhood and it was a passion that would remain with him throughout his life. In the book, ‘Tahiti a Sketchbook’ dedicated to his life and work, his daughter Aiu Deschamps-Boullaire describes the young Jacques thus: ‘…a dreamer who spent his days collecting insects in the garden of the family’s summer house near Reims and his evenings quietly contemplating the images illuminated by the family’s magic lantern in the darkness of the sitting room.’

Though it was traditional in an advantaged position such as his to follow the father and grandfather into the profession of law, this was not to be his course and at any rate the First World War intervened and he became a fighter pilot and remarkably so since he had poor eye-sight and suffered from myopia. Many of his fellow pilots perished but Boullaire survived. He kept in touch with himself as an artist by painting humorous scenes on the body of his plane.

After the war, Jacques, still a young man, could while away his time aided by the luxuries that came from belonging to a family of substantial wealth. All the past-times and the dalliances of the priviledged were available. His sister married Louis Renault, one of the founders of the Renault car company, who had built an incredible fantasy mansion and there he could stay and enjoy the sensuous and romantic delights of a life-style by the sea. Those who knew him accepted himas a dreamer, a thinker, someone of introspection and quiet reverie.

Yet he left the ease and security to begin a new life in Paris with no secure income. He took advertising jobs to survive and Louis Renault, trying to help his brother in law and bring him back into the mainstream, made him Director of Advertising at Renault. It was short lived. Boullaire loved Paris and his life as an artist began in Montmartre. He taught himself the difficult and challenging techniques of making artist’s original prints, first with woodcuts, and then etching onto copper. At this time he came to know and make friends with other print makers: Chiéze, Cami, Decares, and the Englishman, Stanley William Hayter and John Buckland Wright who was originally from New Zealand.

It was also during this period in 1935, that Boullaire met the woman who would inspire him, influence him deeply, and who would become his wife, Anne Hervé; the daughter of the Admistrator of Tuamotus, she had just arrived in Paris after twenty five years living away from European civilization on a Pacific island, and in Paris she walked the streets barefooted. And she too was an artist, a painter, and the two of them could share their passion, increasingly focussing their lives upon simple and naturalistic aims.

And so, to Tahiti. But first of all this was an experience in which, though it was familiar to Anne, Jacques had to find himself. All was so different, the essence of nature there and its powerfully coloured intensity was so different to Paris. The women too were so differnt in their attitude and physical being. On their return to France Boullaire began work on illustrating the ‘Marriage of Loti’. And then Anne gave birth to a daughter that they named ‘Aiv’ which means ‘baby’ in Tahitian.

How grim it must have been for him to be then faced with another war, and with its nullifying effect on the professional art world. He was not to fight in this one, but the family had to survive great hardships with little money. In the south of France they tried to live a life of self-sufficiency, growing their own food, and Anne as a consquence Ane increasingly had less time for her own painting.

After the war the family returned to Paris and Jacques set about working as an illustrator, receiving commissions from publishers of selct editions. Publications included ‘La Symphonie Pastorale’ by André Gide, Flaubert’s ‘Bouvard et Pecouchet’, and Proust’s ‘A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur’.

The life-style of the Boullaire family, its lack of materialism and its simplicity, the love of aesthetics to a degree that evokes the spiritual, the working on the land for self-sufficency during the war, has strong similarities in its aims and ideals to those that became so important to those who were authentically involved in the hippy movement that was to follow later in the century in the 1960s. The Boullaire’s, and it is reminiscent too of the gypsy ways of the earlier English artist, Augustus John, took in the Summer months to living in a caravan and travelling wherever the fancy took them – Boullaire always drawing.

In 1949 the Boullaires returned to Tahiti and this time for a much longer stay; the one year originally planned for turned into four. They made the lon jouney by boat via Portugal, the Antilles, and Panama. Their first sensing of their approach to Tahiti was not from eyesight but from the floral perfume brought to them by the sea breeze. Boullaire travelled through the island, drawing and watercolouring incessantly and perfecting his imagery of the Tahitian people in their naturak relaxed poses and habitat. The life could be idyllic. Jacques got on with the people and though he had little of the language his wife was fluent. He would always try to communicate with them as they allowed him to make his drawings of them, either formally posing (which could bore them), or just going about their ordinary lives. Though the family still tried to be self-sufficient and this took up much of Anne’s time, she too wqas painting again, mainly landscapes in pastel.

In Papeete they were invited by Princess Takau to live in the home of her mother, the queen. On the island of Bora Bora they stayed with their friend Jacqueline and Bernard Villaret and on Moorea they camped out on the beaches.

The family returned to Paris in 1952. He had a final stay in Tahiti fourteen years later and though now he was elderly and with fragile health he still worked.

Boullaire died in Paris in 1972. He was at his desk, still working, an engraving needle in his hand. In this classic image of a Tahitian woman or vahine, the artist skill is at his peak.

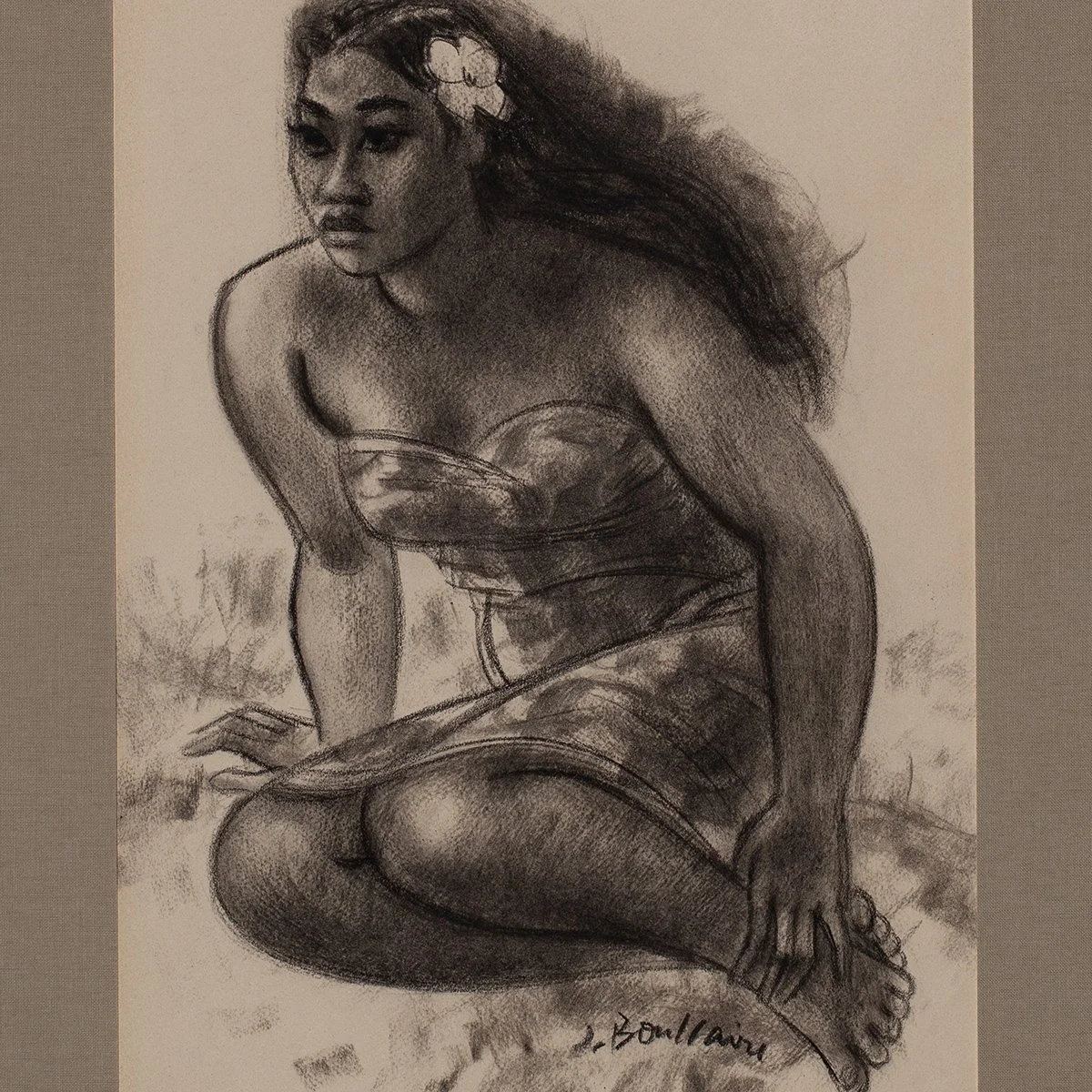

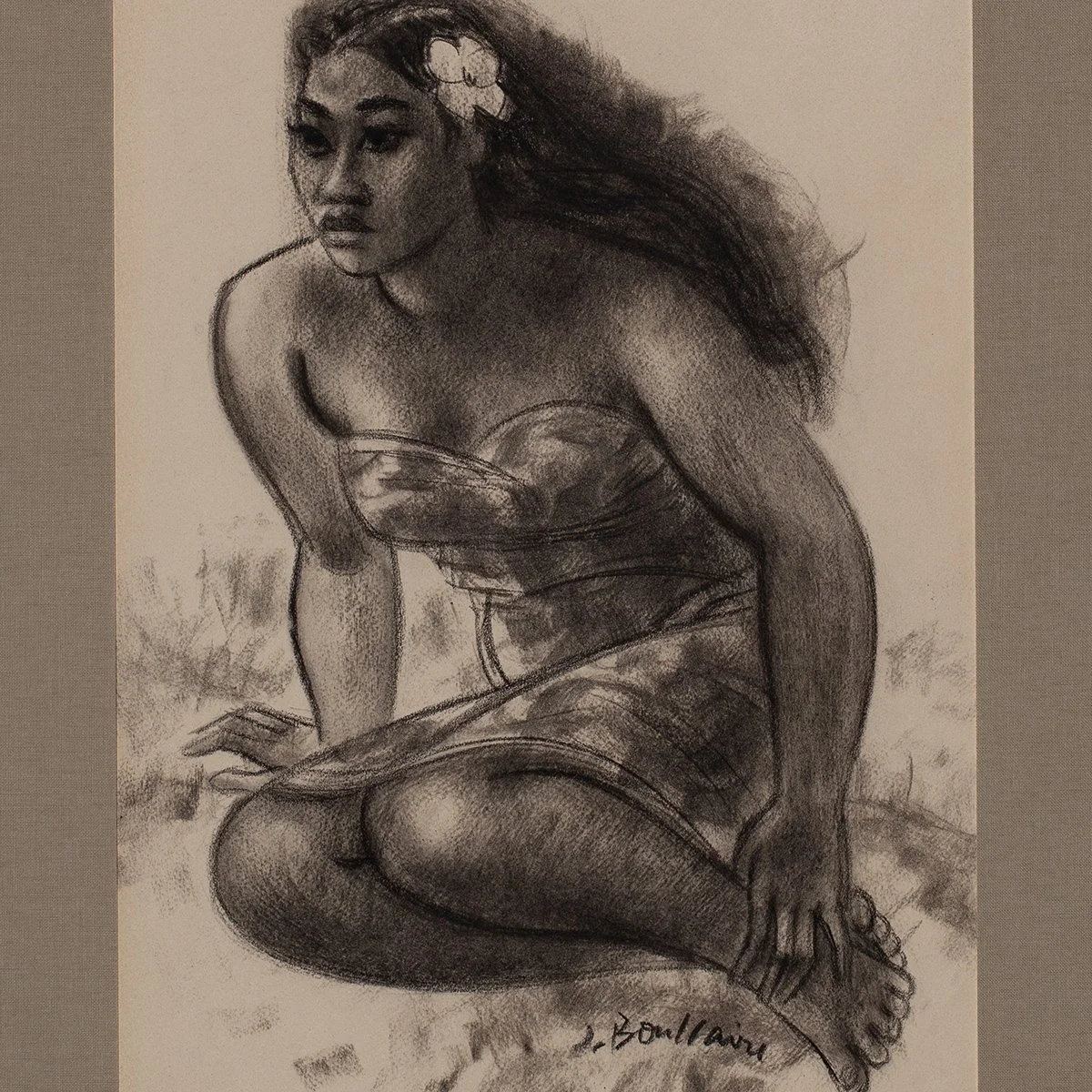

Charcoal on paper

1950s

Height 23" Width 18" including frame, image Height 14 1/2" Width 10"

Provenance: Private collection Paris

Born in 1893, the eldest child of a family of wealthy Parisian lawyers, Jacques Boullaire loved to draw in his childhood and it was a passion that would remain with him throughout his life. In the book, ‘Tahiti a Sketchbook’ dedicated to his life and work, his daughter Aiu Deschamps-Boullaire describes the young Jacques thus: ‘…a dreamer who spent his days collecting insects in the garden of the family’s summer house near Reims and his evenings quietly contemplating the images illuminated by the family’s magic lantern in the darkness of the sitting room.’

Though it was traditional in an advantaged position such as his to follow the father and grandfather into the profession of law, this was not to be his course and at any rate the First World War intervened and he became a fighter pilot and remarkably so since he had poor eye-sight and suffered from myopia. Many of his fellow pilots perished but Boullaire survived. He kept in touch with himself as an artist by painting humorous scenes on the body of his plane.

After the war, Jacques, still a young man, could while away his time aided by the luxuries that came from belonging to a family of substantial wealth. All the past-times and the dalliances of the priviledged were available. His sister married Louis Renault, one of the founders of the Renault car company, who had built an incredible fantasy mansion and there he could stay and enjoy the sensuous and romantic delights of a life-style by the sea. Those who knew him accepted himas a dreamer, a thinker, someone of introspection and quiet reverie.

Yet he left the ease and security to begin a new life in Paris with no secure income. He took advertising jobs to survive and Louis Renault, trying to help his brother in law and bring him back into the mainstream, made him Director of Advertising at Renault. It was short lived. Boullaire loved Paris and his life as an artist began in Montmartre. He taught himself the difficult and challenging techniques of making artist’s original prints, first with woodcuts, and then etching onto copper. At this time he came to know and make friends with other print makers: Chiéze, Cami, Decares, and the Englishman, Stanley William Hayter and John Buckland Wright who was originally from New Zealand.

It was also during this period in 1935, that Boullaire met the woman who would inspire him, influence him deeply, and who would become his wife, Anne Hervé; the daughter of the Admistrator of Tuamotus, she had just arrived in Paris after twenty five years living away from European civilization on a Pacific island, and in Paris she walked the streets barefooted. And she too was an artist, a painter, and the two of them could share their passion, increasingly focussing their lives upon simple and naturalistic aims.

And so, to Tahiti. But first of all this was an experience in which, though it was familiar to Anne, Jacques had to find himself. All was so different, the essence of nature there and its powerfully coloured intensity was so different to Paris. The women too were so differnt in their attitude and physical being. On their return to France Boullaire began work on illustrating the ‘Marriage of Loti’. And then Anne gave birth to a daughter that they named ‘Aiv’ which means ‘baby’ in Tahitian.

How grim it must have been for him to be then faced with another war, and with its nullifying effect on the professional art world. He was not to fight in this one, but the family had to survive great hardships with little money. In the south of France they tried to live a life of self-sufficiency, growing their own food, and Anne as a consquence Ane increasingly had less time for her own painting.

After the war the family returned to Paris and Jacques set about working as an illustrator, receiving commissions from publishers of selct editions. Publications included ‘La Symphonie Pastorale’ by André Gide, Flaubert’s ‘Bouvard et Pecouchet’, and Proust’s ‘A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur’.

The life-style of the Boullaire family, its lack of materialism and its simplicity, the love of aesthetics to a degree that evokes the spiritual, the working on the land for self-sufficency during the war, has strong similarities in its aims and ideals to those that became so important to those who were authentically involved in the hippy movement that was to follow later in the century in the 1960s. The Boullaire’s, and it is reminiscent too of the gypsy ways of the earlier English artist, Augustus John, took in the Summer months to living in a caravan and travelling wherever the fancy took them – Boullaire always drawing.

In 1949 the Boullaires returned to Tahiti and this time for a much longer stay; the one year originally planned for turned into four. They made the lon jouney by boat via Portugal, the Antilles, and Panama. Their first sensing of their approach to Tahiti was not from eyesight but from the floral perfume brought to them by the sea breeze. Boullaire travelled through the island, drawing and watercolouring incessantly and perfecting his imagery of the Tahitian people in their naturak relaxed poses and habitat. The life could be idyllic. Jacques got on with the people and though he had little of the language his wife was fluent. He would always try to communicate with them as they allowed him to make his drawings of them, either formally posing (which could bore them), or just going about their ordinary lives. Though the family still tried to be self-sufficient and this took up much of Anne’s time, she too wqas painting again, mainly landscapes in pastel.

In Papeete they were invited by Princess Takau to live in the home of her mother, the queen. On the island of Bora Bora they stayed with their friend Jacqueline and Bernard Villaret and on Moorea they camped out on the beaches.

The family returned to Paris in 1952. He had a final stay in Tahiti fourteen years later and though now he was elderly and with fragile health he still worked.

Boullaire died in Paris in 1972. He was at his desk, still working, an engraving needle in his hand. In this classic image of a Tahitian woman or vahine, the artist skill is at his peak.